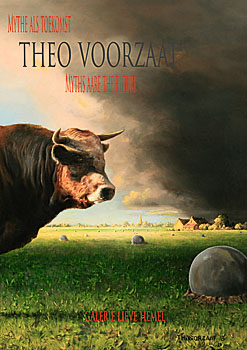

Mythe als toekomst Wie doordenkt over de impact van de ophanden zijnde klimaatveranderingen, beseft dat de mens in staat blijkt te zijn een complete planeet onbewoonbaar te maken. Als we de nadelige kant even buiten beschouwing laten, kun je dat als een verdienste zien, althans, het neemt iets weg van de sensatie die ons bevangt als we 's-nachts bij heldere hemel met onze hoofden in onze nekken naarboven turen, vol ontzag voor de miljarden zonnestelstels waar we op dat moment naar kijken. Het zal even duren, maar nu ligt ook het moment in het verschiet dat het heelal tegen onze strapatsen in bescherming moet worden genomen, als niet al een vergelijkbaar soort wezens ons al voor is. Hoewel de schilderijen van Voorzaat een zekere actualiteit niet ontzegd kan worden, maakt het plezier waarmee hij schildert dat hij zich onttrekt aan een rubricering in de trant van het gedachtengoed, dat wordt geässocieerd met Der Untergang des Abendlandes, met repect overigens voor Oswald Spengler, die als kind van zijn tijd beslist weing plezier beleefd zal hebben aan zijn eigen profetiën, al moet ik toegeven dat ik daar geen onderzoek naar heb gedaan. Meer kans heeft de veronderstelling dat de mens, hoe rampzalig de scenario’s ook zijn waarin hij zich staande moet houden, er zich vervolgens bij neerlegt, dan wel ertegen protesteert, maar er uiteindelijk het beste van maakt. Waaraan ik graag toevoeg dat ik me afvraag wat toch de rechtvaardiging is voor het uitlegbaarheidsstreven. Van de kant van de toeschouwer weet ik een paar gronden. Nieuwsgierigheid is beslist een van de drijvende krachten die de mens immer door doet vragen. Als ik als jongetje luisterde naar andermans verslaggevingen, zei ik steeds, als er een pauze viel, “en toen?”. Dat kwam me tot mijn verbazing op een reprimande te staan. Het aspect waarop ik doel is gebrek aan zelfvertrouwen van de toeschouwer, of dat wat hij of zij spontaan bedenkt, wel oirbaar is en door de beugel kan. Maar natuurlijk, hoeveel kunstenaars zijn niet opgelucht als in plaats van de toch een beetje onbehagelijke vraag over diepere bedoelingen en vooral lagen de toeschouwer spontaal gaat verhalen wat hem in gedachten komt bij het zien van het kunstwerk. Staaft overigens niet de suggestie van geestverwantschap, die dan boven komt drijven, de gewenste impact van het kunstwerk in kwestie? Het is maar een vraag hoor, want ik besef maar al te goed dat al te veel begrip de kunstenaar vervolgens weinig ruimte laat voor een zinvolle maatschappijkritische instelling. Maar dat ook dat weer meevalt leert deze anekdote. Het was in de loop van de jaren negentig dat ik deelnam aan de KunstRai. De leden van de selectiecommissie zaten nog op de basisschool, eh, niet allemaal. Mijn stand grensde aan een shockerend bedoelde presentatie van het Sandberginstituut, waar een paar jonge kunstenaars de vrije hand hadden gekregen. Zij stelden een caravan op, waarin rottend vlees werd gelegd en enkele zwarte bromvliegen werden losgelaten. Daarna werd de caravan verzegeld. Aan het eind van de beurs zag de caravan van binnen zwart van de vliegen. Grappig en macaber tegelijk, twee vliegen in één klap. Maar ik dwaal af. In de loop van de beurs slenterden de kunstenaars van het vliegenproject - de vliegen deden het werk - mijn stand in en bekeken met een mengsel van ontzag, waardering en respect het rijtje schilderijen van Voorzaat, dat uitkeek op de vliegen. Vanuit hun stand observeerden zij hoe drommen mensen zich aan dat rijtje vergaapten, helaas met hun rug naar de vliegen. Maar daar gaat het me niet om. Ik was verrast door de spontane waardering voor het werk van Voorzaat van zulke prominent aktueel gekleurde kunstenaars. Op hun beurt waren de jonge kunstenaars verrast dat er met mij normaal te praten viel, of althans, wat is normaal, maar zij begrepen mijn woorden, die kennelijk niet opriepen tot strijd en verzet, of erger nog, walging. Ik koester die herinnering. Omdat ik even moet nadenken over de relatie tussen kunst en wetenschap staar ik naar buiten. Een groep toeristen passeert, aangevoerd door een gids die onophoudelijk ratelt. De rij is eindeloos lang. Ik zie geen oortjes, en vraag me af wat de volgers meer dan een meter of vijf achter hem, en hem dus niet meer horen, denken of zien. Van de hele rij zag ik één jonge vrouw terloops een blik werpen naar de galerie. Wat me deed beseffen dat het voor hun verbeeldingskracht niet dringend noodzakelijk is ergens geweest te zijn om er iets van te vinden, of eventueel te leren. Maar ik dwaal af. Ik verbaas me over de hardnekkige neiging van kunstenaars zich aan te sluiten bij de wetenschap, wat nu ook weer niet wil zeggen dat er geen verbanden mogen bestaan tussen beide disciplines. Maar kijk, juist dit woord drukt de onverenigbaarheid treffend uit. Wetenschap is eerder dan levenshouding vooral een discipline, waarvan het recept is dat het inzicht komt met vallen en opstaan en eeuwig onderzoeken. Kunst is geen discipline, maar wat dan wel. Kunst onttrekt zich aan alle regels, maar trekt constant zijn sporen door de maatschappij. Natuurlijk zijn er dan ook raakpunten met wetenschap en maatschappelijke betrokkenheid, maar daar horen professoraten, eisen van reproduceerbaarheid en bewezen nut van welk gedachtenspinsel ook niet bij. Dat nut bestaat natuurlijk wel degelijk ook, maar het kan en mag niet voortkomen uit eis of dogma. Het was eind jaren zestig, begin jaren zeventig, dat de Insectensekte zich deed gelden. Een van de drijvende krachten was tandarts Max Reneman. Een van de betrokken kunstenaars en oprichters die ik me herinner, is Theo Kley. (Aanbevolen voor een beter inzicht in dit gebeuren is lezing van onder andere dit artikel in de Groene Amsterdammer Moeder waar zijn de vlinders gebleven ) In die context ontstond min of meer toevallig een opgravingsproject midden in het oude Amsterdam, in een voormalige kroeg, genaamd Karel Appel, waar men midden in de gelagkamer een kuil was gaan graven, op een oude waterput stuitte, en maandenlang met hulp van ieder die maar wilde, voorwerpen en vooral fragmenten naarboven bracht. Ik weet nu pas een woord dat ongeveer omschrijft wat men daar opgroef - het was verwondering. Er onstonden rijtjes restanten rond een meterdiep gat, dat technisch gezien beter gestut had kunnen worden. Het hele gebeuren was ontegenzeggelijk geënt op degelijke gewoonten van geologisch onderzoek, maar alles was net iets anders, maar wat er niet was, dat was een uitkomst. Nu was dat project niet exemplarisch voor wat men in die tijd als kunst beschouwde, wat het wel zou zijn als het nu gebeurde. Maar als ik u gerust kan stellen, ik kom er niet uit en onthoud me van een oordeel. In een droom zag ik het voor me: de realisatie van de Voorzaatiaanse verbeeldingswereld, met nieuw gebouwde en gereconstrueerde ruïnes, ooit door Voorzaat geschilderd en nu op die uitgestrekte locatie, met rondom donkere luchten en zonsondergangen middels projecties, en een overvloed aan onverklaarbare lichtbronnen. Mijn gedachten dwalen af naar het waarom. Kunst zou geen verwoordbaar waarom moeten hebben. Waarom niet? Een waarom pretendeert de waarheid. De universele waarheid bestaat niet, de beleving van de waarheid wel. Dat is wat anders dan de leugen. Het besef van het bestaan van talloze waarheden behoeft empathie. Empathie houdt ook in dat met persoonlijke inzichten voorzichtig wordt omgesprongen. Idealiter is empathie twee-zijdig. Zo niet, dan vormen geduld en bescheidenheid de beste tussentijdse oplossing. Wie stelt dat het woord waarheid hier verkeerd is gekozen, heeft gelijk, maar voor degene waarvoor die waarheid geldt, ligt dat anders, en die heeft dus ook gelijk. Maar ik dwaal af. Terug naar het museum met de door Voorzaat geschilderde ruïnes, dat waarschijnlijk altijd imaginair zal blijven. Hoewel, als de schadelijkheid van het vliegen voor het leefbaar houden van de aarde is te beschouwen als voorbode van een totale omschakeling van wat we als toeristen gewend zijn, namelijk dat het nog slechts bij uitzondering mogelijk is bezienswaardigheden in levende lijve te bezoeken - alleen als je er per fiets of per trein kunt komen - en dat we het in de toekomst voornamelijk zullen moeten doen met hologrammen van de pyramides en de Chinese Muur. Bij nader inzien is er toch best een kans dat dat ruïnemuseum à la Voorzaat er zal komen. En o ja, de moraal van het verhaal is dat u een ander perspectief krijgt aangereikt van waaruit u de schilderijen van Theo Voorzaat kunt beschouwen. Echte uitleg is dat niet, maar het geeft u op eigen kracht toch meer inzicht. Myths are the future

You only need to think through the impact of the imminent changes to our climate to appreciate that it is not beyond mankind to render an entire planet uninhabitable. Leaving to one side for the moment the downside of this faculty of ours, one could see it as an achievement of sorts, in that it takes something away from the sense of wonder that grips us when we stare into the clear night sky, heads tilted back, crick in neck, in awe of the billions of solar systems in plain view. We’re not quite there yet, but the moment will undoubtedly come when the universe will need protecting from our shenanigans, provided a flock of creatures similar to us do not pip us to the post where this is concerned. Although Theo Voorzaat’s paintings undeniably possess an element of topicality, the sheer joy he derives from painting enables him to avoid being pigeonholed in terms of notions of the “Decline of the West” variety – with all due respect, I hasten to add, to Oswald Spengler, who as a child of his time cannot have derived much (if any) succour from his own prophecies, although I must confess that this is not something I myself have researched. On a more promising note, there is the presumption that regardless of the disastrousness of the scenarios mankind may be finding itself pitted against, it will go on either to resign or rally and, ultimately, make the best of a bad thing. To which I would add that the penchant for finding justification that is so frequently found in those who are artistically “in the know” has always puzzled me. Adopting the spectator’s perspective has provided me with an insight into some of the reasons for such chronic “explanitis”. Curiosity is most definitely an example of a driving force that keeps urging people to ask questions. When as a child I was listening to someone else’s account of something or other that had occurred, I remember saying “and then what?” whenever the narrator paused. To my dismay this invariably earned me a rebuke. The aspect I’m getting at is the lack of confidence on the part of the spectator as to whether what he or she comes up with on the spur of the moment is acceptable and appropriate. Then again, does not many an artist experience a sense of relief when the spectator, rather than honing in on the somewhat awkward aspect of deeper meanings, not to mention “layering”, launches into what comes to his or her mind when looking at the work? And does not the ensuing suggestion of kindred spirits corroborate the sought-after impact of the work in question? Don’t mind me, I’m just asking, for I know all too well that an excess of empathy may leave the artist little room to come up with a constructive socially critical stance of his or her own. The following anecdote shows, however, that it need not be as bad as all this. As a participant, sometime during the Nineties, in the KunstRai Art Fair (most members of whose current Selection Committee, by the way, were still safely ensconced in primary school at the time), I found myself occupying a booth next door to a shock-seeking presentation by the Sandberg Institute, in the context of which a handful of aspiring young artists had been given free rein. Their display featured a caravan in which some putrid meat had been placed and several bluebottles had been released, after which the caravan had been hermetically sealed. By the end of the art fair, the entire inside of the caravan was coated in flies, in a display which was as whacky as it was macabre. The point was, however, that there came a moment during the art fair – while the flies were going at it hammer and tongs – when the artists behind the Fly Project sauntered into my booth, where they spent some time looking in awe, approval and deference at the row of paintings by Theo Voorzaat across from the flies. Back in the safety of their own booth they observed throngs of people – their backs unfortunately facing the flies – marvelling at the row of paintings. My point is that I had not expected such conspicuously “woke” artists to show such instinctive appreciation for Voorzaat’s work, and they for their part were equally surprised to find me so easy to talk to, in that as their conversational partner I was using words they recognised as being free from belligerence, resistance and, worse still, distaste. It was an experience the memory of which I will cherish forever. As I am gathering my thoughts about the interrelationship between art and science, I find myself staring out of the window and into the street, where a troupe of tourists happen to be trudging by in near-endless procession, headed by a tour guide who never stops talking. As I can’t spot any earpieces, it makes me wonder what must be going through the minds, and eyes, of all those who due to their not being at the very front of the line will not be able to understand a word their tour guide is saying. I spot a single young woman casting a cursory glance at my shop window and realise that it is thanks to the imaginative powers of the human mind that one does not necessarily have to have been somewhere in order to form an opinion or – where appropriate – pick up a pointer or two from the experience. But let’s get back to where I left off. One thing that never ceases to amaze me is how relentlessly hell-bent artists can be on forging a scientific affiliation, which is not to say that the two disciplines cannot (or should not) entertain any links at all. The very word “discipline” adequately expresses what is so utterly incompatible about the two. Science first and foremost is something disciplinary rather than attitudinal. The scientific recipe insists that it is only through plenty of trial and error and endless research that enlightenment can be achieved. Art by contrast is not a discipline … but what is it instead? Art sidesteps all the rules while constantly leaving its marks on society. And although this makes it inevitable that art on the one hand and science and social awareness on the other should interface, art does not need any professorship, reproducibility requirement or proven benefit of any web of thoughts whatsoever. Of course there most certainly is a benefit to art, but it is a benefit which cannot, and must not, manifest itself as a command. It was in the late Sixties to early Seventies that the Insect Cult, one of whose driving forces was a dentist-cum-artist named Max Reneman, blazed a trail. Theo Kley is one of the names I remember of associated artists and founders. (The weekly newsmagazine ”Groene Amsterdammer” in a 2015 article whose title translates as “Mother, where have the butterflies gone” (https://www/groene.nl/artikel/moeder-waar-zijn-de-vlinders-gebleven) devoted in-depth attention to the movement.) It was in this context that an excavation project sort of randomly came about in Amsterdam’s old city centre, the “dig” in question being situated on the premises of what used to be a bar named after Karel Appel, where a handful of people, having started digging up the tap-room floor, chanced upon an ancient water well from which (mostly fragments of) artefacts were retrieved over the next months by anyone who felt like having a go. It is only now that I have found a word that comes close to describing what was actually dug up at the time: “wonderment”. An array of bits and pieces gradually formed around what slowly but surely developed into a seriously deep hole (and one which from a structural safety point of view would have benefited from being shored up using struts). Although the entire enterprise was undeniably based on tried and tested geological research methods, the whole approach was slightly off kilter. The one thing that proved elusive was an end result. I would point out that as a project the “dig” was not exemplary of what was regarded as “art” at the time (which, by the way, it would be had it taken place today) – but if it’s any comfort to you, rest assured that I can’t work it out and am reserving judgement. It came to me in a dream: the realisation of the imaginary-world-according-to-Theo-Voorzaat, with newly constructed and reconstructed distinctive ruins having in the distant past been painted by the artist and having ended up in this vast setting, surrounded by projection-generated dark skies and sunsets, and an abundance of inexplicable light sources. I am aware that my thoughts are straying to the “why”. Art should not come with a verbalisable “why” … but for what reason? “Why” is suggestive of truth. Although there is no such thing as the “universal truth”, the experience of the truth can be very real. Then again, the untruth is a whole new kettle of fish. The realisation that numerous truths exist calls for empathy, which in turn implies that personal insights should be dealt with in a delicate manner. Empathy should ideally be a two-way street, with patience and modesty offering a decent interim solution where duality remains elusive. You would not be wrong if you characterised the word “truth” as a misnomer in this context. Then again, the person whose truth it concerns will naturally see things very differently, which cannot but make him or her every bit as “un-wrong” as you. Back to the business at hand. Back to the museum – an imaginary museum for ever more, I expect – featuring the ruins painted by Theo Voorzaat. Then again, in so far as the harmful impact of air travel on the future liveability of the planet can be regarded as a harbinger of a 180 degree change in the tourist experience, “seeing the sights” may in future be the preserve of cyclists and train travellers only, with everyone else having to make do with holograms of the great pyramids and the Chinese Wall, which on second thought lends some likelihood to the eventual emergence of the “museum of ruins in the manner of Theo Voorzaat”. And let’s not forget the moral of the story or rather, the alternative viewpoint you are presented with, for you to look at Theo Voorzaat’s paintings from a different angle. It’s hardly a genuine explanation, but it will help you deepen your insight, all by yourself. |

|

BACK