Pareltjes IV Bekende en onbekende schilderijen uit de tweede helft van de vorige eeuw van: Hendrick Brandtsoen † Hans van der Kroef C.B. Muller Olav Cleofas van Overbeek Peter van Poppel Herman van Rossum † Karel Sirag Theo Voorzaat

De oudste schilderijen in deze tentoonstelling dateren uit de zeventiger jaren van de vorige eeuw. Ook al is dat niet lang geleden, toch is menige klant van na die tijd. Dat maakt dat ik kan mijmeren alsof ik zelf al eeuwen meega. Tentoonstellingen als deze geeft dat een bijzondere glans. Ik heb het gevoel iets tijdloos te doen, en ook alsof het me gegund is voor de tweede keer te mogen werken aan de reputatie van een kunstenaar, in het bijzonder als die al is overleden. In deze tentoonstelling zijn dat Hendrick Brandtsoen en Herman van Rossum. Onder andere doordat er van hen nooit meer nieuwe schilderijen zullen komen, beleef ik hun werk anders. Laat ik proberen het aan de hand van een vijftiende-eeuws schilderij uit te leggen. Kent u de naam Petrus Christus? Ik heb favoriete schilders en favoriete schilderijen. Dat zijn verschillende werelden. Van sommige schilderijen weet ik de naam van de schilder niet eens, of zocht ik er niet naar en kwam ik er bij toeval achter. Dat gaat dan wel meestal om vijftiende- en zestiende-eeuwse schilders, zoals in dit geval. Ik ken het schilderij van een wenskaart, die thuis al zeker vijf jaar op mijn bureau staat. Pas na jaren zocht ik op de achterkant van de kaart naar de naam van de schilder, die me niets zei. Ik beschrijf hier twee belevingen, op grond van hetzelfde schilderij. De eerste is dat ik iets van grote schoonheid onbenoemd laat, zonder verhaal, als zo zuiver mogelijke emotie, die visueel tot me komt. Ook nu ik meer weet van de schilder - voornamelijk dat er weinig over hem bekend is - weet ik niets over het schilderij. Het is een portret van een jonge vrouw, die je in de ogen kijkt, maar haar hoofd iets naar opzij heeft gedraaid. Haar huid is onwaarschijnlijk glad, op een geraffineerde manier naïef geschilderd, door de tand des tijds gelijkmatig en bijna teder gecraqueleerd. Het gladde van haar huid wordt nog geaccentueerd door haar naar achter getrokken haren, die zijn verborgen in een groot naar achter hellend hoofddeksel, vanwaar een stevige band onder haar kin door loopt. Haar oogleden hebben de schijn van mongoloïde trekken, maar ook dat kan een aspect van die geraffineerde naïeve manier van schilderen zijn. Zij kijkt wantrouwend, laatdunkend, behoedzaam, ontgoocheld, van alles een beetje. Het deert me allemaal niet, zelfs het craquelé niet. Met wat zorg gaat het schilderij nog wel duizend jaar mee. Over duizend jaar gesproken, dat brengt me op die tweede beleving, dat ik me afvraag wat er door het hoofd gaat van deze vrouw, en of dat in bepaalde opzichten misschien niet anders is dan nu. Dat ik kijk naar een wezen dat net zo goed in deze tijd geleefd zou kunnen hebben, dat mij voorhoudt dat ik me niet moet verbeelden dat zij niet weet wat de eeuwen na haar brengen zullen. Maar dat het haar wel frustreert. Waarna ik terugstap in mijn eigen werkelijkheid, al blijf ik mijmeren over de schilderkunst. Daar rommelt het op verschillende fronten, maar voor nu beperk ik me tot de schildersmaterialen. De receptuur is veranderd, pigmenten worden verboden, het vernissen gaat niet zoals het hoort. De ondergrond maakt van het precieze schilderen een nachtmerrie, want glaceren - dat is vele dunne transparante verflaagjes over elkaar aanbrengen - mislukt dikwijls. Willen uit die veranderingen schilderijen voortkomen, die over duizend jaar nog te genieten zijn, dan zullen receptuur, en vooral ingrediënten, juist niet mogen veranderen. Wat me ingaf dat die al eeuwenoude schildertechnieken en verfrecepten veiliggesteld zouden kunnen worden door ze op te nemen in de canon van het cultureel erfgoed. Waarmee, grappig genoeg, die alles verslindende vernieuwingsdrang als contrast genietbaarder wordt. Het vreemde is dat het overgrote deel van de schilders afhankelijk is van verffabrieken. Zij die zelf hun verf maken zijn zeldaam. Ik heb ooit eens een schilder aangehoord, die na jaren van onderzoek meende het recept van Jan van Eyck te hebben doorgrond, maar een decennium later zag ik een klein schilderijtje van zijn hand, waarvan het oppervlak tot in alle hoeken door craquelé was ontsierd. Niet dat ik hem iets verwijt, het zoeken naar die oude receptuur blijft een avontuur op zich, maar je weet pas dat het niet werkt als het te laat is. De tand des tijds gaat ook aan mij niet voorbij, maar ach, aan wie niet? Je wordt ouder, de tijd verstrijkt steeds sneller, je gaat stilstaan bij dingen die lang geleden in je eigen leven gebeurden, al lijkt het of dat een soort eergisteren is. En je verbaast je steeds meer om de hype van het nieuwe. Vergis u niet, ik hou gretig alle nieuwe ontwikkelingen bij, voor zover dat binnen mijn bereik ligt en mijn expertise me daartoe in staat stelt, dus wijst u mij niet na met "hij houdt het niet meer bij". Het is wat anders. Het lijkt of je in staat bent geheel op eigen gezag, wars van mode en rumoer, te bepalen wat uit je verleden van waarde was, ongeacht of het toen de waardering kreeg die het toen al verdiende. Ik denk dat het gevoel u bekend voorkomt. En dan vooral als het destijds verdronk En dan vooral als dat bijzondere destijds verdronk tussen de wanen en de tranen van de dag, of dat het juist bijna zó gewoon was, dat je zo nu en dan bijna ging twijfelen aan je eigen beoordelingsvermogen. Zodat je nu alsnog begrijpt dat het geren en gedraaf nog steeds norm is, met de bijbehorende onderschatting, cultuurbreed, om me nou maar even te beperken tot de wereld van de beeldende kunsten. Zodat het organiseren van de "Pareltjes"-tentoonstellingen me alleen al een voldaan gevoel geeft omdat ik er alsnog weer iets aan kan doen. Dat ik voor de tweede keer die door de tijd dwarrelende snippers van genialiteit onder de aandacht mag brengen. Dat ik kan inbreken in de hedendaagse vluchtigheid, dat ik de makers van al dat moois een extra flard van waardering mee kan geven, in de hoop dat de toekomst uiteindelijk oordeelt dat de rode lijn uit het verleden altijd van waarde en van toepassing blijft, al wordt decennialang het tegendeel geroepen door andere bevlogenen. Top Little Treasures IV Known and unknown paintings from the second half of the twentieth century by: Hendrick Brandtsoen † Hans van der Kroef C.B. Muller Olav Cleofas van Overbeek Peter van Poppel † Herman van Rossum † Karel Sirag Theo Voorzaat †

The earliest paintings forming part of this exhibition date back to the nineteen seventies, which admittedly is not that long ago, but long enough nevertheless to predate quite a few of you, my customers. This gives me the freedom to let my mind wander, sort of as if I have been around for ever, which in turn lends that extra bit of lustre to exhibitions such as this, making me feel as they do that I am involved in something that transcends time, and giving me the opportunity once more to contribute to an artistic reputation, all the more so where the artist in question is no longer among us. The fact that both Hendrick Brandtsoen and Herman van Rossum, some of whose works this exhibition features, have passed on has precluded all possibility of new creations ever being added to their respective bodies of work. Let me try to clarify myself using a fifteenth-century painting as an example. I don’t know if you have ever heard of Petrus Christus, the “Renaissance Master of Bruges”. I have my own personal “gallery” of favourite painters and favourite paintings, and he is in it. There are paintings – most of them from the fifteenth to seventeenth century era – of which I don’t even know who made them, as much as there are artists’ names I have chanced upon when I wasn’t even trying. I owe my introduction to the work of Petrus Christus to a greeting card which I was given several years ago and which I’ve kept on the desk in my study ever since. Several years passed until one day I found myself scrutinising the reverse of the card in an attempt to find out the painter’s name – which, as it turned out, did not ring any bells with me at all at that time. These are two different experiences based on one and the same painting, the first of which is that of leaving something of overwhelming beauty nameless, without a story, as the purest possible, visually induced emotion. Even though I have since found out a bit more about the artist – mainly that not much at all is known about him – I know as little now as I did then about the actual painting, which depicts a young girl who looks you in the eye, her head turned away ever so slightly. Her impossibly smooth skin, painted in a sophisticatedly naïve manner, over time has been evenly adorned with a near-tender craquelure. The opalescence of her skin is enhanced by the fact that her hair has been pulled off her face and tucked away underneath her “hennin”, the sizeable headdress of the day with its backward tilt and sturdy chin strap. Her eyelids appear to lend a slightly Mongolian aspect to her face, or perhaps it is yet another aspect of the painter’s sophisticatedly naïve technique. Her expression is one of wariness, disdain, guardedness, disenchantment – a little bit of everything, in fact. None of this bothers me, not even the craquelure: this is a painting which – treated with a bit of tender loving care – will withstand the test of time for another thousand years at least. Which brings me to the second experience: that of my wondering what the girl in the painting is thinking and whether what is going through her mind might not be exactly the same in some ways if she were among us today. I am, in short, looking at someone who could easily have been a contemporary, who is telling me not to flatter myself into thinking that she has no idea of what the centuries will bring after she is gone, ticked off as she might be by this very circumstance. Back to my own reality, albeit that it does not stop me ruminating on the art of painting. Although there is no shortage of talking points, I will for now confine myself to painting materials. Recipes have changed, pigments are being banned, varnishing is not happening the way it should. Fine-painting has become something of a nightmare due to the substrate now that glazing – the application, one on top of the other, of a succession of ultra-thin, transparent layers of paint – does not nearly always pan out. In order for these changes to yield paintings that can still be admired a thousand years from now, the formulations and, more importantly, the ingredients should be kept as they have always been. Which got me to thinking that this body of centuries-old painting techniques and paint formulations could be safeguarded for ever by adding them to the cultural heritage canon … which amusingly enough would render the all-consuming urge to innovate more palatable by contrast. The funny thing is that the vast majority of painters depend on paint manufacturers. Those who fabricate their own paints are few and far between. I remember a conversation with a painter who after many years of research was convinced he had reconstructed the recipe once used by none other than Jan van Eyck. When ten years later I came across a small portrait he had painted, I noticed that the entire surface had been defaced by a web of craquelure. Not that I would hold it against him, it being an adventure in itself to try and recover ancient paint formulations, but you only know that you have failed when it’s too late to do anything about it. None of us are immune to the ravages of time. You get older, time goes by faster and faster, you finds yourself thinking about things that happened when you were much younger, even though it feels as if it was only the day before yesterday … and you find yourself wondering more and more about the hype of what’s new. Let there be no mistake: I do everything I can to keep up with what’s happening in so far as my expertise allows, so don’t dismiss me as someone who has lost touch. What this is about is the ability completely independently and without being influenced by craze or clamour to decide which experiences in one’s past have been of value, whether or not they were given the appreciation they deserved at the time. You must know the feeling, particularly where it concerns that something very special which at the time was drowned out by the issues and injuries of the (then) day, or something that was almost too commonplace , so much so that it made you all but doubt your own soundness of judgment. All of which has finally enabled you to appreciate – better late than never – that the same hullaballoo, and the denigration it implies, is still the norm today from one end of the cultural spectrum to the other (just to confine myself for now to the visual arts). So that the organisation of the “Known and unknown Treasures” exhibitions leaves me with a sense of gratification at having been allowed once more to contribute, by drumming up attention (for a second time, no less) for all these slivers of genius from decades past, at being able to cut in on the triteness of the day, to confer an extra little bit of grateful appreciation on the makers of all these delightful creations, in the hope that the future will decide that the common theme from the past will never forfeit its relevance, as something which decades of dissenting opinions have not been able to change. |

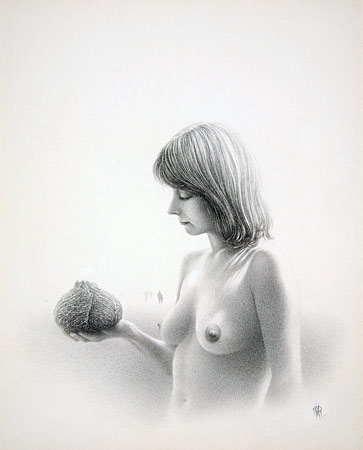

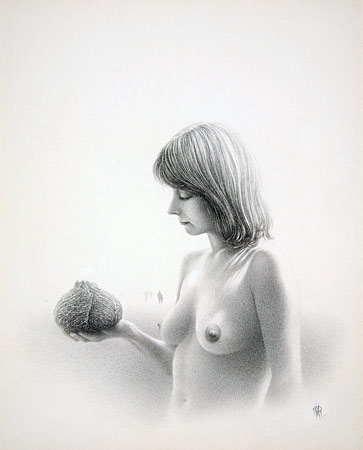

Herman van Rossum (1952-1991) heeft zich in zijn korte leven ontwikkeld van surrealist tot, zoals ik het graag omschrijf, als de schilder van de stilste mist van Nederland. Dat ook het surreële zich in dit subtiele spel van groen en eindeloos wit zich bleef manifesteren is des te merkwaardiger. Maar kijk eens naar de vrouw in "Verwachting". Zij is vermoedelijk Nederlandse, modieus in de tijd dat ze werd geschilderd, in 1977. Ik weet dat het buitenproportioneel klinkt, u gelooft het pas als u in het schilderij kruipt, te klein haast om te zien, maar het is bijna een tijdgenote van het Meisje met de Parel van Vermeer. Mag ik dat wel zeggen? Het landschap zwijgt immers ook? Er is prachtige mist. Die in de loop der jaren nog mooier werd, onmogelijk mooi, onbeschrijfelijk mooi.  Hendrick Brandtsoen (1938-2003), een erudiete maatschappij-kritische Vlaming, was naar de normen van de kunstwereld op een ongewone manier tegendraads. Aan vernieuwing had hij geen boodschap, de zeventiende-eeuwers zou hij evenaren! Maar ongemerkt sloop het hedendaagse toch in zijn in aanvankelijk zeer klassieke stillevens. Zijn oeuvre is klein, elk schilderij was een bevalling, tot meer dan vijf tot zes schilderijen per jaar kwam hij niet. Ik denk, nee, ik weet zeker dat naarmate de afstand in tijd groter wordt, zijn schilderijen, op het eerste gezicht uit een andere tijd, maar in feite op de vierkante millimeter verweven met het heden, toch als baanbrekend zullen worden gezien. In aanmerking genomen dat hoe ouder de fysieke receptuur is, hoe moeilijker het is zich te onttrekken aan dat patroon. Alles overboord gooien is veel makkelijker dan zich een weg zoeken tussen de relicten uit een roemrijk verleden. Het is nauwelijks meer dan hier en daar een accent verschuiven, in compositie zowel als belichting, in het gebruik van ruimte en nadruk. En dat alles weer vanuit het persoonlijke perspectief, zoals dat bij scheppende mensen staat voor zowel totale vrijheid als bijna dwangn€tische noodzaak om het innerlijk brandende vuur als enige leidraad te houden. Zo'n mentaal microproces kan niet anders dan geleidelijk verlopen, net zo goed als het zich bewust worden van die bizarre spagaat. Het zal hem ooit als een grote verdienste worden nagedragen.  Herman van Rossum (1952-1991) over the course of his brief life transformed himself from a surrealist to “the painter of the most tranquil mist in the Netherlands”, as I like to phrase it, which makes it all the more remarkable to see the surreal having continued to adorn the artist’s subtle interplay of greens and never-ending whites. But let’s take a closer look at the female figure in the painting called “Expecting”. She comes across as Dutch and would definitely have been “on trend” at the time she was painted, in 1977. I know it sounds disproportionate and you won’t believe it until you have actually wriggled your way into the painting, on such a tiny scale that it is barely discernible, but she could in passing be mistaken for a contemporary of Vermeer’s “Girl with the Pearl Earring”. Can I say this? The landscape is keeping mum, mist reigning supreme in all its glory – mist that over the years has become increasingly and impossibly glorious, to the point where it has come to defy description.  Hendrick Brandtsoen (1938-2003) was a critical Flemish citizen from a scholarly background, whose attitude when vetted against the artistic world’s standards was one of curious contrariness. He held no truck at all with innovation – what he strived for was to emulate the seventeenth-century greats. And yet he couldn’t stop the contemporary gradually insinuating itself into his still lifes, as classical as they started out as. The body of work he left on his passing is modestly sized: as every new painting was as much of a herculean task for him as the previous one had been, his annual production never exceeded five to six paintings at the most. I think, no, I know for sure that as the temporal distance lengthens, his paintings – which at first glance may appear dated but which in fact are steeped in the present, down to the last square inch – will sooner or later be recognised as ground-breaking, taking into consideration that the older the formulation in physical terms, the harder it becomes to evade the traditional pattern. Discarding everything is so much easier than negotiating one’s way among the relics of a glorious past. It is barely more than the odd accent shift, in terms of both composition and exposure, in the use of both space and highlight, all of this from the personal perspective that in creative folk harnesses boundless freedom and a near-n€tic compulsive need to make sure that the fire burning inside should be, and continue to be, one’s sole guideline. A micro process of the mind such as this cannot but unfold gradually, as much as gaining awareness of this bizarre quandary has to be a gradual process. The time will come when credit for his great achievement will be given where credit has always been due. |

Top