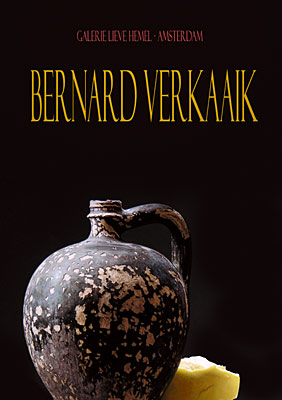

Alles Stroomt

Deze catalogus is verschenen ter gelegenheid van de tentoonstelling van Bernard Verkaaik, 30 september t/m 29 oktober 2017, en is samengesteld en geschreven door Koen Nieuwendijk. (16 pagina's, 27 afbeeldingen in kleur, ISBN 978-90-70402-51-8)

Deze catalogus is verschenen ter gelegenheid van de tentoonstelling van Bernard Verkaaik, 30 september t/m 29 oktober 2017, en is samengesteld en geschreven door Koen Nieuwendijk. (16 pagina's, 27 afbeeldingen in kleur, ISBN 978-90-70402-51-8)

Hoe tegenstrijdig kan een woord zijn. Stilleven in de traditionele betekenis is een aanduiding van een categorie naar onderwerp, zoals realisme dat is naar stijl. Het woord stilleven is iets specifieker over de inhoud, maar dat is misleidend. De Franse taal gaat daar het verst in, die spreekt van nature morte. Van de wetenschap hebben we geleerd dat de hersenen nooit stilstaan. Denk aan uw dromen, en het woord chaos ligt op het puntje van uw tong. En dan zou de menselijke blik, gericht op een stilleven, borg staan voor leegte, stilte, dood?

Het woord stilleven heeft al meningeen verleid tot een woordspeling bij het benoemen van een tentoonstelling, zoals ik in 1991 deed met de uit stillevens van kunstenaars van de galerie samengestelde tentoonstelling “Zichtbare Stilte”, die behalve Het Slot Zeist ook het Drents Museum aandeed. De vraag is echter of die aanname van stilte aangaande de psychosomatiche verwerking van de opgedane indrukken wel een juiste weergave is van het menselijke verwerkingsproces. In gemoede vraag ik mij af wat er gebeurt in de hersenen van een persoon, tijdens het waarnemen van een als adembenemend ervaren stilleven. Als ik probeer het gevoel te beschrijven, dan komen woorden als "de tijd staat stil" in mij op. Ik vraag me af of dat een afspiegeling is van het proces dat op dat moment in de hersenen plaats vindt. Mocht ik willen voldoen aan norm van de maatschappelijke relevantie, dan zou ik misschien beweren dat die hersenen zich herschikken naar een staat van evenwicht, zoals de denkende mens die graag ervaart. Dat zou kunnen betekenen dat tijdens het kijken ervaringen en inzichten worden ingedeeld als meer of minder heilzaam om meteen of later te worden gebruikt. Een drukte van belang dus.

Maar kunt u zich ook voorstellen dat ik persoonlijk niet ben gecharmeerd van het ontleden van weldadige ervaringen? Met velen vind ik dat het leven geconsumeerd moet worden, waaraan richtlijnen, handleidingen, recepten en adviezen beslist kunnen bijdragen. Wat mij betreft hoort kunst niet in dit rijtje thuis. Of nee, nou moet ik mijzelf corrigeren. Kunst mag alles, dus ook bijdragen aan het rendement van het bestaansbeleven. Maar tegelijk moet kunst niets. Ik wil niet, in de euforie tijdens het waarnemen van een prachtig stilleven, moeten gaan zoeken naar elementen van maatschappelijke relevantie, ten einde mijzelf ervan te verzekeren dat ik naar kunst kijk, en niet naar een mooie, maar nietszeggende afbeelding. In feite is het onwenselijk dat de huidige stand van de kunstbeoordeling een dergelijke innerlijke dialoog oproept. Nou moet ik mijzelf alweer corrigeren. Maar natuurlijk mag kunst ook deze innerlijke dialoog oproepen, maar het dwangmatige ervan zit me toch dwars.

Bekijken we het woord stil vanuit de kant van de maker, dan rijst een heel ander beeld op. De voorgeschiedenis van Bernard Verkaaik (1946), van voordat hij zich bekeerde tot het stilleven en niets dan het stilleven, kan toch niet anders dan tumultueus genoemd worden. In de vorige eeuw was Verkaaik een gevierd illustrator, deels omdat hij zich kon botvieren op het exploiteren van zijn technisch talent, deels omdat de esthetiek toch voortdurend onherroepelijk om de hoek kwam kijken, die - want gevoelsmatig gefundeerd - met bijna dwangmatige kracht werd verdedigd tegen de restricties en inzichten uit de hoek van de opdrachtgever. Men dient zich ook te realiseren dat de digitale revolutie nog niet was losgebarsten, waardoor de branche in hoge mate afhankelijk was van het pure handwerk, van echt talent. Tijdens zijn opleiding heeft Pierre Jansen, toen docent op de Academie voor Beeldende Kunst in Rotterdam, eens een uur lang gefascineerd toegekeken hoe Verkaaik met verf en lucifers een vis tekende. Voor zo’n expressieve persoon in feite een groot impliciet compliment.

Wat de maatschappelijke en culturele implicaties ook mogen zijn, er bestaat onder illustratoren van oudsher een diep verlangen om na een arbeidzaam leven de lonkende horizon van de onafhankelijkheid over te klauteren, wat uiteindelijk toch maar weinigen lukt. Dat legt twee aspecten bloot. Ten eerste, dat er veel illustratoren zijn, die als het aan hen ligt, hun esthetische en morele maatstaven botvieren op het werk dat zij in opdracht verrichten, en ten tweede, dat de claim van kunstenaars van totale ongebondenheid maatschappelijk-ideologisch gezien een veel breder draagvlak heeft dan uit de matrijs van het dagelijkse denken valt op te maken.

In dat beeld past dat een kunstenaar ongebonden is, en een illustrator in opdracht werkt. Voor de overzichtelijkheid stel ik het een beetje gechargeerd, maar in de praktijk hebben we hier in wezen te maken met geïnstitueerde vooroordelen. Op zich is er geen bezwaar tegen vooroordelen, al was het maar omdat absolute objectiviteit niet bestaat, ware het niet dat die ten grondslag liggen aan onterechte claims, die helaas kunnen uitgroeien tot onterechte gevoelens van superioriteit. Zou iemand beweren dat een illustrator kan wedijveren met een vernieuwende kunstenaar, dan zou er een storm van protest opsteken.

Ik laat die ook even voor wat het is, en trek u mee in de gevoelswereld van een illustrator, die zich voortdurend opdrachten gelegen moet laten liggen, waar de kunstenaar zich op de borst mag kloppen vanwege een totale onafhankelijkheid. Of het een beter is dan het ander kan desgewenst worden beargumenteerd met de aanname dat de meeste opdrachtgevers handelen vanuit het perspectief van het maken van winst. Het feit dat de meeste kunstenaars er maar met moeite in slagen brood op de plank te krijgen ondersteunt de ideologische kant van hun bezigheden, maar de gelukkigen onder hen kunnen zich meten met getalenteerde voetballers. Of dat een reden is te twijfelen aan hun integriteit? Welnee, dat zou betekenen dat veel geld genereren synoniem is met karakterloosheid. Het bestaat natuurlijk wel, maar om het daarmee tot norm te verklaren gaat te ver.

Pas als de de armoede zelf gekozen is, zoals door nonnen, die bij hun intrede trouwden met God en afstand deden van alle aardse bezittingen, ontstaat kans op het hardmaken van een hoger normbesef. Zouden die getalenteerde voetballers ook eens moeten proberen, de kans dat Ajax of Feyenoord de wereldcup winnen is dan aanzienlijk groter, dus hoeveel miljoen mensen doe je daar niet een immens plezier mee? Alhoewel, nou spreek ik mijzelf tegen, verdedigde ik niet immers een paar regels terug dat aardse rijkdom kan samengaan met hoog normbesef? Maar ik dwaal af.

Waar ik op aanstuur is dat de keuze van Verkaaik om ondanks zijn succesvolle carrière als illustrator te kiezen voor het onzekere bestaan van kunstschilder (ook dit is inmiddels in de wereld van beeldende kunst een archaïsche typering), wat tegelijk weer in tegenspraak is met de vigerende opvatting binnen het gareel van de nieuwe normen van schurende relevantie, waar het schilderen van stillevens per definitie wordt beschouwd als inhoudsloos en als alternatief van het drukken van geld. Het is juist die opvatting die mij stimuleert de achtergronden en de impact van de stap van Verkaaik zichtbaar te maken. Zijn afkeer tegen het dwingende karakter maakt namelijk, door zich eraan te onttrekken, de eronder verborgen en bijkans mystieke laag van het streven naar een staat van fysieke zuiverheid als geestelijke beleving zichtbaar. Waarmee in één moeite door wordt aangegeven dat kunst meer is dan het streven naar maatschappelijke relevantie, die op zich terecht knabbelt aan de marges van de menselijke idealen, maar van zichzelf veel te vluchtig is om volledig recht te doen wedervaren aan de mentale dommekrachten van de menselijke geest.

Voor Verkaaik is verval het summum van schoonheid. Hoewel dat niet het juiste woord is. Slijtage, aantasting, beschadiging, dingen die in het dagelijks leven heel gewoon zijn, maar worden weg-geïdealiseerd, dat komt meer in de buurt. Volmaaktheid bestaat maar even, een schaars moment, absoluut het aanschouwen en het beleven waard, maar tevens prominent aankondiger van wat spoedig volgt: krassen, deuken, bladders, barsten, scherven, rimpels, gruis en stof. Als dat geen toveren is: het proces van natuurlijk verval - inclusief het menselijk ingrijpen - opnieuw transformeren in adembenemende schoonheid. Want dat doet Bernard Verkaaik met zijn door het leven en de elementen getekende potten.

Ondanks strijd en tumult beleefde Verkaaik wel degelijk plezier aan het commercieële illustratiewerk, maar uiteindelijk gingen de irritaties dermate overheersen dat hij brak met zijn succesvolle loopbaan en zijn heil zocht in het ongebonden bestaan van kunstenaar.

Dat bleek nog weer hardere strijd op te leveren. Waar tijdens het illustreren het gras aan de andere kant van de heuvel altijd groener leek te zijn, bleek het fantoom van het ideaal in eerste instantie ongrijpbaar.

Pas in de loop van een jaren durend proces groeide zijn eigen identiteit, waarbij geestelijke ascese zowel richtlijn als gemoedstoestand werden. Ook dat was strijd, net zoals al eerder het breken met zijn eigen succesfomule Verkaaik weer terugwierp naar de status van de droge boterham. Al schrijvende betrap ik me op het toetsen van mijn eigen woorden aan het art speak syndroom, waar mee ik bedoel mooie en plechtige woorden die een dusdanige abstractie aannemen, dat als er niet een lap verklarende tekst aan wordt toegevoegd - niet zelden nog onbegrijpelijker - de goegemeente zich vertwijfeld afvraagt waar ik het over heb. Dus daarom dit duidelijke beeld: een bloem in een pot zal Verkaaik niet gauw meer schilderen. Het moge zijn dat een dergelijk ensemble mooi oogt, bij hem zal de pot het - beschadigd en wel - alleen moeten doen. Daaraan is ook het gebrek aan inzicht van zijn epigonen te herkennen: die beginnen bij wijze van spreken met er een bloem in te zetten. Natuurlijk weet Verkaaik heel goed dat het kijkend publiek die bloem in eerste instantie mooier en romantischer vindt, maar juist het behagen om het behagen heeft hij achter zich gelaten. Emotionele intensiteit geschreven in olieverf, balans door ascese, spoor van menselijk handelen als detail, dat al is nu zijn gereedschap. Al wie daarvoor openstaat is welkom.

|

|